|

Up

Up

Making the

Making the

Aerodrome

Airworthy

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

n

Hammondsport, Curtiss’ workmen had been working exclusively on the “America,”

a flying boat designed to make a record-setting flight across the

Atlantic Ocean. Curtiss had them set this aside and everyone

concentrated on the Aerodrome. Charles Manly, who had built the

Aerodrome engine, joined the team along with Albert Zahm, who was

the Smithsonian’s on-site representative. They briefly discussed

building a copy of the original catapult Langley had used in 1903,

but decided it would save effort to launch the Aerodrome from

pontoons. The team struggled mightily to get the Aerodrome ready on

time, but was plagued by unanticipated problems. The airframe was

much weaker than expected and had to be strengthened. In addition to

replacing the ribs and adding spars, Curtiss extended the outriggers

that mounted the pontoons, adding wire rigging between the

outriggers and the wing spars much the same way the upper and lower

wings of a biplane are rigged. This created a trusswork that braced

the wings for about a third of their length. n

Hammondsport, Curtiss’ workmen had been working exclusively on the “America,”

a flying boat designed to make a record-setting flight across the

Atlantic Ocean. Curtiss had them set this aside and everyone

concentrated on the Aerodrome. Charles Manly, who had built the

Aerodrome engine, joined the team along with Albert Zahm, who was

the Smithsonian’s on-site representative. They briefly discussed

building a copy of the original catapult Langley had used in 1903,

but decided it would save effort to launch the Aerodrome from

pontoons. The team struggled mightily to get the Aerodrome ready on

time, but was plagued by unanticipated problems. The airframe was

much weaker than expected and had to be strengthened. In addition to

replacing the ribs and adding spars, Curtiss extended the outriggers

that mounted the pontoons, adding wire rigging between the

outriggers and the wing spars much the same way the upper and lower

wings of a biplane are rigged. This created a trusswork that braced

the wings for about a third of their length.

The old Manly-Balzer

engine would not operate properly and the propellers did not produce

enough thrust. Curtiss replaced the original dry-cell battery

ignition with a high-tension magneto, and the primitive box-shaped

drip carburetor with a modern float-regulated carburetor. Still the

engine would not produce the necessary RPMs, so Curtiss trimmed the

propellers to give them a more modern shape with less drag.

The original

controls were two small wheel-cranks beside the pilot’s seat. The

forward wheel moved the "steering rudder" beneath the aircraft left

and right for yaw control; the rear wheel moved the Penaud tail up

and down for pitch. There was no roll control; Langely had depended

on a pronounced dihedral angle between the wings to provide roll

stability. These controls could not possibly respond in time to what

Curtiss knew to be the demands of aviation, so he replaced them with

a standard Curtiss wheel, post, and yoke. He linked the rudder to

the yoke at first, and then switched to the wheel. The tail was

linked to the control post. Eventually, he locked the rudder in

place and modified the Aerodrome’s Penaud tail to move side to side

as well as up and down.

By the time

Curtiss had worked out these solutions, Langley Day had come and

gone. He was not confident enough to attempt his first mission – to

show that the Aerodrome might have flown in 1903 – until late May.

By this time the Aerodrome was no longer the same aircraft it had

been in 1903; even a casual comparison of photos that Brewer and

others took in June 1914 with those taken of Aerodrome in 1903 shows

this to be the case. (Compare the 1903 and 1914 Aerodrome drawings

HERE.)

But Curtiss, Walcott, and the Hammondsport team would say that it

was close enough, some of them until they day they died.

Curtiss made a

few straight-ahead hops on May 28, June 2 and June 5, none lasting

more than a few seconds. These were not the results he and Walcott

had hoped for, but the media had their story and the photos to

support it. Walcott was quick to press the political advantage.

Within a week – 11 June 1914 – and while these news stories were

still fresh in the minds of legislators, House Minority Leader James

R. Mann of Illinois read into the Congressional record the results

of the Hammondsport trials. He then asserted the need to “provide

under some scientific bureau of the Government some means for

further investigations and experiments with regard to

heavier-than-air Machines.” Mann intimated that this “scientific

bureau” should be under the direction of the Smithsonian

Institution, as suggested by its Secretary. He also mentioned a

dollar amount, “…$50,000 to continue investigations along the line

of aeronautics under the Smithsonian Institution.” Nothing was

decided, but the point was made.

As for Curtiss,

he set the Aerodrome aside for a few weeks while he ramped up the

America project again, and then began the second part of his

mission – to see what value, if any, the tandem wing configuration

might have for modern aeronautics. The tests continued, albeit at a

more leisurely rate and under new management. When he was certain

the America was back on track, Curtiss bowed out and went to

Buffalo, New York to set up a new factory. Albert Zahm took over the

testing of the Aerodrome.

It was apparent

to all who attended the initial test flights that the original

Manly-Balzer engine didn’t have the oomph to get the Aerodrome in

the air and keep it there. Among the first things that Zahm and his

crew did was swap out the old radial for a new Curtiss 80 hp V-8.

They also scrapped the twin pusher propellers and replaced them with

a single tractor screw. Flights resumed in September of 1914 and the

Aerodrome performed much better. Curtiss pilot Gink Doherty was able

to keep the machine aloft for distances up to half a mile, reaching

an altitude of 30 feet. And the machine continued to evolve. Zahm

and crew experimented with its center of gravity, control linkages,

the diameter and pitch of the propeller, number and position of the

pontoons, the length of the secondary spars, and a dozen other

details. In March 1915 while Lake Keuka was still frozen, they

swapped the pontoons for skates, reducing weight and drag.

Eventually they were able to fly 20 miles – the length of the lake.

But throughout all this experimentation, the Curtiss team was never

able to navigate the Aerodrome. Of the three pilots who eventually

flew the aircraft – Glenn Curtiss, Elwood Doherty, and Walter

Johnson. – none ever made a successful turn of more than a few

degrees.

In early June of

1915, Orville’s brother Lorin visited Hammondsport under an assumed

name and observed several Aerodrome flights before he was found out.

As luck would have it, he witnessed a flight in which the rear A-frame

that supported the wing rigging were swapped out for something

approaching the original

guy post. The back wings collapsed in flight, just as they had

during a launch attempt in 1903. The photographs he took were

confiscated, but he was able to note this change and many others

that had been made to the Aerodrome up to that time. And there were

probably more changes after that. The flight tests continued until

November 1915 when Curtiss called a halt. The Aerodrome was

disassembled, packed up, and returned to the Smithsonian.

|

Left to right: Charles Manly, Glenn Curtiss, and Albert Zahm with

the rebuilt airframe of the Aerodrome.

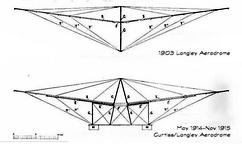

These drawings by Griffith Brewer show the rigging of the original

Aerodrome and the rigging of rebuilt Aerodrome that was flown by

Curtiss.

This "taxi test" (without wings) on 27 May 1914, clearly shows the extensions to

the airframe that helped brace the wings.

After the June 1914 flights, the original Aerodrome engine and

pusher propellers were replace with an 80 hp Curtiss motor turning a

single tractor airscrew.

The Aerodrome on a take-off run on September 17, 1914 with a new

engine and propeller. Note the tail dragging in the water. The tail

was later raised not only to keep it from getting wet but also to

give it greater freedom of movement.

The position of the pilot was also changed. Note that the shoulder

yoke has been removed, the pilot is using just the wheel and the

post to steer the aircraft. In all, three pilots flew the modified

Aerodrome – Glenn Curtiss, Elwood "Gink" Doherty (shown), and

Walter Johnson.

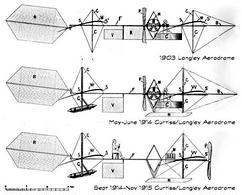

Top: The original configuration of the Aerodrome. Middle: The

aircraft during the first phase of the Hammondsport tests when

Curtiss and Walcott were trying to show that the "original"

Aerodrome was airworthy. Bottom: The aircraft during the second

phase when the "tandem configuration" was tested.

|