|

Up

Up

An Idea Whose

An Idea Whose

Time Had Come

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

s

Walcott was slowly rebuilding Langley’s reputation, the Wright

brothers’ was being eroded. They had been international celebrities

and national heroes in 1909. But this changed when they filed a law

suit for patent infringement and began to ask royalties not just

from aircraft manufacturers, but also producers of aviation events

and even individual exhibition pilots. Pilots and plane-makers that

had once admired the Wrights now carefully followed the patent suits

and rooted against the brothers. Editorials appeared that condemned

the Wrights for their apparent greed and attempts to monopolize this

fragile new industry. To the general public, the Wrights were made

to look less like heroes and more like aspiring robber barons. s

Walcott was slowly rebuilding Langley’s reputation, the Wright

brothers’ was being eroded. They had been international celebrities

and national heroes in 1909. But this changed when they filed a law

suit for patent infringement and began to ask royalties not just

from aircraft manufacturers, but also producers of aviation events

and even individual exhibition pilots. Pilots and plane-makers that

had once admired the Wrights now carefully followed the patent suits

and rooted against the brothers. Editorials appeared that condemned

the Wrights for their apparent greed and attempts to monopolize this

fragile new industry. To the general public, the Wrights were made

to look less like heroes and more like aspiring robber barons.

This was the

situation in January of 1914 when a panel of three justices on the

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit upheld Judge Hazel’s

decision that the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to have

infringed on Patent No. 821,393 – the Wright brothers’ 1906 patent

on an aircraft control system. They also upheld his judgment that

the patent was entitled to “liberal interpretation” as it was the

grandfather or “pioneer” patent of the aviation industry.

It was an

electrifying decision for the entire aviation community; the

decision made it possible for Orville Wright (Wilbur was now

deceased) to create a patent monopoly on the airplane, the same as

Alexander Graham Bell had done with the telephone.

The Wright

Company’s board of directors met in New York immediately after the

decision was announced and proposed to do just that by hiring

William F. McComb – a confidant of the President Woodrow Wilson with

deep Democratic connections – to lobby the administration to buy

Wright aircraft. Orville balked. He did not want his company or the

aviation industry tied to a particular political party. He did not

want to manage a colossal manufacturing operation, nor did he want

to build one by bankrupting dozens of other companies. He began to

plot a way to shed himself of his corporate obligations and the

burden of the Wright patent. In the meantime, he let it be known

through the New York Times he was willing to work with any

aircraft manufacturer who was willing to pay 20% of the purchase

price to license their aircraft. This was the same percentage that

the Wright Company had charged Burgess and others who had licensed

their patents and designs – in short, it was business as usual.

Usual or not,

20% was a financial impossibility for most U.S. airplane

manufacturers prior to World War I; none of them were that

prosperous. Had it been enforced it would have put most of them out

of business, creating a monopoly through attrition. The news seemed

even worse for Curtiss, if that were possible. Other airplane

companies might be able to negotiate royalties and payments, but

there was too much bad blood between Orville Wright and Glenn

Curtiss for Curtiss to expect any mercy. Wilbur had run himself

ragged defending the Wright patent in court, then contracted typhoid

fever while on one of his many trips. His worn down physical

condition almost certainly made him more

susceptible and more likely to succumb to the disease, and the

Wright family held Curtiss indirectly responsible for Wilbur's

death.

That same month, Lincoln Beachey, a well-known aviator and a

stockholder in the Curtiss company, wrote to the Smithsonian and

asked for the loan of the remains of Aerodrome A. His

proposal was to restore the airframe, then mount a modern motor and

propellers and attempt to fly the old aircraft. It was not a new

idea; Bell, Chanute, and members of the U.S. Army had all suggested

something similar as early as 1906 – a good number of people in

Washington believed that the Aerodrome was not a failure; it simply

had been improperly launched. Walcott had actually written to

Curtiss about making another launch attempt prior to

Beachey’s

inquiry; it seemed a good initial project for the Langley

Aerodynamical Laboratory. Walcott turned Beachey down, but the

letter started a ball rolling.

Walcott could

not help but notice that news and editorials concerning the “patent

wars” had damaged Orville Wright’s reputation. The country had just

spent the better part of a decade trust-busting with President

Theodore Roosevelt to level the economic playing field for smaller

companies. The word “monopoly” had a stink about it, even if it was

supported by the courts. If the Aerodrome flew, it would show that

manned aircraft could have flown before the Wrights; their patent

had no right to pioneer status, and the suit would go back to the

courts. Not only would Langley be rehabilitated; the Smithsonian

would be seen as having saved the aircraft industry. It might be the

big win needed to procure some serious funding for the Langley

Aerodynamical Laboratory

Not long

afterwards, Walcott invited Curtiss to bring one of his new flying

boats to Washington for Langley Day – 6 May 1914. Curtiss, who was

aware of Beachey’s proposal, replied that he would rather restore

and fly the Aerodrome. There was a series of phone calls between

Curtiss, Bell, and Walcott as the project began to take shape. There

would be two separate missions, the first to show that the 1903

Aerodrome was airworthy and the second to investigate the properties

of the tandem-wing configuration. On March 25, Walcott told Bell

that Curtiss could reproduce the Aerodrome for $2000. It was a

bargain-basement estimate; it's almost certain that Curtiss proposed

such a low cost because he stood to gain so much from the project.

Then Bell and Walcott discussed whether it was proper for the

Smithsonian to fund the experiment, given its possible commercial

impact. To avoid that hornet’s nest, Walcott volunteered $1000 of

his own money and Bell offered to chip in the rest.

On March 30,

Walcott, Bell, and Curtiss met at Bell’s home in Washington. Walcott

wanted the Aerodrome replica ready to fly by Langley Day – May 6,

1914. Curtiss could not guarantee that he could get it done that

quickly, and Walcott suggested it might be faster to rebuild the

original Aerodrome. After all, the central frame was ready to go; it

had been repaired by Charles Manly, Langley’s assistant, before it

was stored. Bell objected, arguing that the 1903 Aerodrome A

was a valuable historic artifact. But technically it was not; the

Aerodrome was still the property of the U.S. Army and some members

of that Army had indicated that they would like to see the machine

fully tested. Walcott prevailed, expedience was paramount, and on

April 2 the Smithsonian shipped the original Aerodrome airframe to

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company in Hammondsport, New York. This

was followed by the original engine several days later. All parties

agreed that this project should proceed in confidence, with no

announcement. The Smithsonian Board of Regents was never consulted

or asked to approve these actions, although Bell was a member of

this board.

|

Although the Wright patent was simply titled "Flying Machine," it

was specifically concerned with aircraft controls – the

control surfaces and the manner in which these surfaces were moved.

These made it possible to navigate the airplane, which in turn made

it a practical form of transportation.

Lincoln Beachey in the cockpit of his Curtiss-built "Beachey Special

Looper."

Beachey racing Barney Oldfield, a popular race car driver, at an

exhibition. The reason that Walcott turned Beachey down may have

been that Beachey was too much of a showman and Walcott wanted the

Aerodrome flights to have the appearance of a serious scientific

investigation.

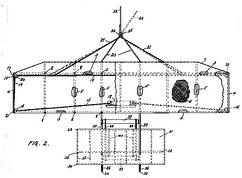

The Aerodrome airframe, top view

The Aerodrome airframe from the side. This was the portion of the

aircraft that Many restored in 1904 before the machine was put in

storage.

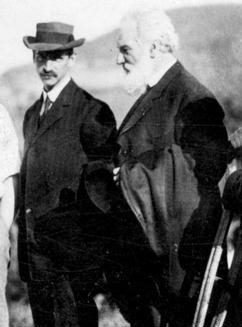

Glenn Curtiss (left) with Alexander Graham Bell (right) and other

members of the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA), standing beside

the White Wing, one of several airplanes the group built in 1907,

1908, and 1909. Bell had introduced Curtiss to aeronautical

engineering and in many ways considered Curtiss to be a protégé.

|