|

Up

Up

Jump-Starting

Jump-Starting

The Langley

Laboratory

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

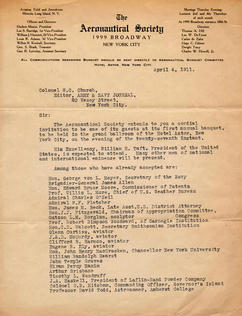

n

1911, at the inaugural banquet of the American Aeronautical Society

in New York City the attendees – Walcott among them – earnestly

discussed creating a “central aerodynamics laboratory” with a board

of advisors to direct the research in this emerging technology.

European nations already had similar organizations such as Britain’s

Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and France’s Central

Establishment for Military Aeronautics. Proposals were floated in

the press and before members of Congress with the U.S. Navy,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bureau of Standards, and the

Smithsonian all vying for control of the proposed institution.

Outgoing President Taft established a committee to study the matter

in 1912, but its efforts came to nothing. n

1911, at the inaugural banquet of the American Aeronautical Society

in New York City the attendees – Walcott among them – earnestly

discussed creating a “central aerodynamics laboratory” with a board

of advisors to direct the research in this emerging technology.

European nations already had similar organizations such as Britain’s

Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and France’s Central

Establishment for Military Aeronautics. Proposals were floated in

the press and before members of Congress with the U.S. Navy,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bureau of Standards, and the

Smithsonian all vying for control of the proposed institution.

Outgoing President Taft established a committee to study the matter

in 1912, but its efforts came to nothing.

In February

1913, a month after President Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated,

Walcott reopened Langley’s workshop at the Smithsonian, contracting

Albert Zahm to run it. Zahm was an aeronautics pioneer himself. He

had built the first wind tunnel in America at Catholic University in

1901, beginning operation just two months before the Wrights built

their tunnel. Zahm immediately began casting around for something

for the reincarnated Langley Aerodynamical Laboratory to do. It was

proposed that the Smithsonian erect a new building complete with

wind tunnels to replace the small workshop, but Walcott could not

raise the funding

On May 6 – “Langley Day,” according to a decree by the Smithsonian –

Glenn Curtiss was awarded the Langley Medal. This time Alexander

Graham Bell gave a speech that actually mentioned the

accomplishments of the recipient, although Walcott used the same

occasion to unveil a bronze tablet at the Castle that lionized

Langley’s contributions to aeronautics. Specifically, it

immortalized Langley's discovery of the "relations of speed and

angles of inclination to the lifting power of surfaces moving in the

air." While Langley had done research in this area, the effect was

actually discovered by a French artillery officer, Col. Du Chemin,

in 1829.

On May 23 of

that year, Walcott convened a committee to direct the workshop,

calling it the “Advisory Committee of the Langley Aerodynamical

Laboratory.” Walcott was the president, Zahm was the recorder, and

the rest of the committee was peopled with high-profile names in

aviation, among them Orville Wright and Glenn Curtiss.

All of this was bold politics. By

reopening the workshop and creating a capable governing body,

Walcott told Congress in effect, “Why create a new national

laboratory for aerodynamics when we’ve already got one up and

running?” The Langley Medal and the commemorative tablet emphasized

Langley’s successes. Even Langley Day (May 6) was calculated to draw

focus away from the failure of the 1903 Aerodrome A – 6 May

1896 was the date that Langley made his first successful flights

with unmanned aerodromes.

But

it didn’t work. Walcott’s opponents found an obscure law passed a

few years earlier that prevented executive agencies such as the

Smithsonian “from requesting the heads of departments to permit

members of their respective departments to meet at the Institution

and serve on an advisory committee.” They used this to force Walcott

to disband his Advisory Committee. Although Langley's workshop

remained open, it no longer had the political status afforded by the

famous and well-placed advisors.

In Their Own Words

|

An invitation to the 1911 Aeronautical Society banquet. This was a

big deal, as evidenced by the guest list. The Society was an

off-shoot of the Aero Club of America, having organized in 1908 for

the purpose of promoting and advancing the science of aeronautics.

The formation of a national laboratory was high on their agenda.

Langley's workshop in the South Shed of the Smithsonian, circa 1900.

The Langley Medal that was awarded to Glenn Curtiss.

The Langley Tablet unveiled at the Smithsonian in 1913.

|