|

Up

Up

Aerodrome

Aerodrome

Beginnings

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

harles

Walcott had been deeply involved with the Aerodrome long before the

Hammondsport trials. He had, in fact, played a vital role in its

inception in 1898. By that time, he had been a player in Washington

for nearly two decades. Walcott had joined the United States

Geological Survey (USGS) as “employee #20” in 1879 and quickly rose

through the ranks. Not only did he write three ground-breaking works

on paleontology in the span of a decade, he was adept at working

with organizations outside the USGS. He organized the Smithsonian’s

growing fossil collection and produced a massive paleontological

exhibit for Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. harles

Walcott had been deeply involved with the Aerodrome long before the

Hammondsport trials. He had, in fact, played a vital role in its

inception in 1898. By that time, he had been a player in Washington

for nearly two decades. Walcott had joined the United States

Geological Survey (USGS) as “employee #20” in 1879 and quickly rose

through the ranks. Not only did he write three ground-breaking works

on paleontology in the span of a decade, he was adept at working

with organizations outside the USGS. He organized the Smithsonian’s

growing fossil collection and produced a massive paleontological

exhibit for Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition.

In 1894, the

Director of the USGS, Major John Wesley Powell, fell afoul of

Congress over policies that restricted the development of western

lands. He was forced to resign and Walcott was appointed to the

directorship, not because he was the most senior or the most

accomplished scientist at the USGS, but because it was generally

agreed that he had the political acumen to repair links with

Congress. That trust was well-founded. By 1898, Walcott had doubled

the size and responsibilities of the USGS, as well as its allotted

funding. He had also cultivated many useful friendships around town

and was on a first-name basis with President William McKinley.

In 1897, George

Brown Goode, the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution,

died unexpectedly. The Smith keenly felt his loss. Goode, an

accomplished naturalist, historian and author, was the first

director of the National Museum and was being groomed for the top

position. Secretary

Samuel

P. Langley, who had been in charge since 1887, was a popular

figurehead. Every American was thankful to him for making the

railroads run on time – he had established time zones and then

telegraphed accurate time data (based on astronomical observations)

to the railroad stations. His subsequent discovery of sun spots and

exciting experiments with unmanned flying “aerodromes” had kept him

in the news and made the Smithsonian a household word. But his

micromanagement and autocratic airs limited his effectiveness as a

leader, and his reclusiveness and aversion to publicity diminished

him politically. By contrast, Goode was a respected and energetic

leader, a brilliant planner and organizer, and the Smithsonian’s

best political asset. With Goode gone, the Smith was in trouble.

The Smithsonian

Board of Regents offered the Assistant Secretary position to Walcott

knowing he was one of the few who could fill Goode’s shoes. He

wouldn’t even have to move – the USGS offices were in the

Smithsonian’s overcrowded National Museum building. After much

cajoling, Walcott agreed to take on the position in addition to his

USGS duties only until another suitable candidate could be found.

Once in the saddle, he attacked the problems he saw with

characteristic energy and immediately began reorganizing the museum,

instituting an administrative system that lasts to this day.

The Smithsonian

of 1897 was not the powerhouse that now dominates the Mall in the

center of Washington DC. It had been ignored and underfunded by

Congress since its inception in 1846. The Institution was the result

of a decade-long debate of what to do with James Smithson’s

half-million-dollar bequest to the United States of America for “the

increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.” Its central building,

nicknamed “The Castle,” was built in 1855. The National Museum

Building was built nearby in 1881, mostly to house exhibits left

over from the 1876 Centennial International Exposition of

Philadelphia – the first World’s Fair. By the end of the nineteenth

century, the Smithsonian was crippled by a lack of space. Langley

had added a zoological park – the National Zoo – in 1889, but that

had done nothing to alleviate the overcrowding.

Walcott was

well-aware than the Smithsonian needed to expand, and was equally

mindful that it needed the support of Congress to do so. It must

have occurred to him that a big win for the Smith would go a long

way’s toward polishing its reputation and attracting political

support. In February of 1898, two events combined that allowed him

to produce that win. First, the February edition of Popular

Science published a laudatory biography of Walcott that

ratcheted his reputation up several notches. And second, the

explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor that same

month caused the U.S. military to inventory its weapons as war with

Spain became imminent. In his diary, Walcott described what happened

next:

-

March 21, 1898 – Walcott runs across

Langley in his workshop, which was proximate to Walcott’s

paleontology lab. They discuss adapting Langley’s aerodrome

design to carry a man. Langley is positive; says such as thing

could be of great service to his country.

-

March 22, 1898 – Walcott meets Langley

again and asks if he was serious about building a manned

aerodrome. Langley says, “Yes, if the money could be secured.”

-

March 24, 1898 – Walcott calls on President

McKinley and tells him about the “Langley flying machine.”

McKinley suggests he talk to Secretary of War George de Rue Meiklejohn and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore

Roosevelt.

-

March 25, 1898 – Walcott meets with

Roosevelt. Roosevelt pens a memorandum to other members of the

War Department saying, “…the machine has worked. It seems to me

worthwhile for this government to try whether or not it will

work on a large enough scale to be of use in the event of war.”

In April,

Roosevelt convened a committee with members from the Army, Navy, and

civilian sector. After discussions with Langley, the committee

recommended pursuing a manned aerodrome and forwarded their

recommendation to the Army and Navy. The Navy declined, saying that an airplane would likely be of

more use on land. But the Army bit and in November it assigned

Langley the task of developing a manned airplane for military use. They agreed to fund the program for $50,000 –

$25,000 in 1898 and another $25,000 in 1899 if sufficient progress

was made. It was also

supposed to be a secret program, but an account of the Langley's

windfall appeared in the newspaper the very next day.

And it was big

news, Just the funding was an earth-shaking accomplishment. The War Department’s

Board of Ordinance, which provided the money, had never before

invested in the actual development of a technology. They were

legendary misers; hoarders that had defied President Abraham Lincoln

and delayed the distribution of repeating rifles to the U.S. Army

during the American Civil War on the grounds that they would “waste

bullets.” In getting them to fund a speculative experiment, Langley

– with Walcott’s initiative – had moved a mountain. And this

achievement had its desired effect. In 1902, while Langley’s star

was still on the rise, Congress agreed to erect a new building for

the National Museum, directly across the Mall from the Smithsonian

Castle.

|

Charles Walcott discovered the Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies

and the mother load of fossils it contained from the Cambrian

period, 505 million years ago.

A Marrella Splendens or

"Lace Crab" fossil, excavated by Walcott. Eventually, he would

uncover over 65,000 specimens of Cambrian life from the shale.

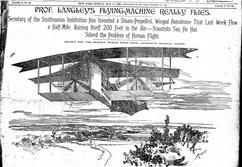

Langley's unmanned Aerodrome No. 5, was successfully launched on 6

May 1896. The Smithsonian would eventually declare 6 May as "Langley

Day."

Langley's aerodrome flights made good copy for the media – and good

public relations for the Smithsonian – as this New York World story

indicates.

The Smithsonian "Castle" (right) and the Arts and Industries

Building (left). Until 1911, these two buildings comprised most of

the office and exhibit space in the Smithsonian.

Both Langley's aeronautical workshop and Walcott's paleontological

laboratory were in the South Shed, behind the Castle.

Assistant Secretary to the Navy Theodore Roosevelt in 1897.

|