|

Up

Up

Escalation

Escalation

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

he

Smithsonian did not answer Northcliffe’s accusations. They pointedly

ignored the Albert Medal presentation and continued to promote

Langley’s Aerodrome as the first true airplane. Their contention

seemed on its way to becoming accepted aviation history, a prospect

which rankled Griffith Brewer as much as it did Orville Wright. The

Englishman decided to take another stab at setting the record

straight. he

Smithsonian did not answer Northcliffe’s accusations. They pointedly

ignored the Albert Medal presentation and continued to promote

Langley’s Aerodrome as the first true airplane. Their contention

seemed on its way to becoming accepted aviation history, a prospect

which rankled Griffith Brewer as much as it did Orville Wright. The

Englishman decided to take another stab at setting the record

straight.

On 21 October 1921, Brewer gave a

speech to the Royal Academy of Sciences in London, England titled

“Aviation’s Greatest Controversy.” In it, he charged “the

Hammondsport trials have been inaccurately reported to the

Smithsonian Institution. An official report declaring that the

Langley machine had been flown at Hammondsport has since been issued

by the Smithsonian Institution.” He described the changes that had

been necessary to convert the Aerodrome into an airworthy machine,

and for the first time divided them into alterations that had been

made prior to May-June 1914, and those that had been made afterward.

He also told how the Aerodrome was restored to its original

condition at the Smithsonian, then labeled as the first true

airplane, Brewer said unequivocally “…both the Smithsonian reports

and the inscription on the machine are misleading and untrue. No

attempt was made at Hammondsport to fly the original Langley

machine.” This speech was simultaneously published in the October

edition of the U.S. Air Service Journal, along with rebuttals from

Charles Walcott and Albert Zahm. The November issue carried

rebuttals from Charles Manly and Glenn Curtiss.

Because Brewer

was a patent attorney for the Wrights, some dismissed his attack as

mercenary. However, there was no mercenary effect.

The position of the Smithsonian Institution

at that time represented little hazard to the value of the British

patents; the government had paid its one-time fee. Neither did it

affect the American patents; the NACA/MAA patent pool had both

validated those patents and neutralized their alleged economic

threat. Brewer was simply exposing an untruth and correcting the

historical record as he saw it.

Brewer’s speech

and its rebuttals created a furor. It galvanized Orville, who up to

this time had presumed the Smithsonian was misled by Curtiss and

Zahm. But Walcott’s response to Brewer’s speech had made it clear

that the Smithsonian was partly responsible for the deception, which

hardened Orville in his position. While both sides of the

controversy dug in, Brewer suggested a drastic course of action,

fighting politics with politics – banish the original 1903 Wright

Flyer I, arguably the most precious historic artifact in

aviation, to the Science Museum in Kensington, England’s equivalent

of the Smithsonian. As early as 1920, Sir Henry Lyons, the director

of the Science Museum, had asked to exhibit the Flyer for a short

time while his curators made precise measurements and drawings so

they could build an exact replica of the aircraft. Orville had

promised to supply the drawings himself, but he never seemed to get

around to it. In 1923, Brewer approached both Orville and Lyons with

a proposal to exhibit the Flyer in England permanently.

Since Orville

had begun to exhibit the restored aircraft, several American museums

had offered to give the Flyer a home, but none with the prestige of

the Smithsonian. The Science Museum had the status that Orville

wanted; and although it wasn’t his native land, England had proved

loyal and supportive. He responded to Brewer, “If I were to receive

a proposition from the officers of the Kensington Museum offering to

provide our 1903 machine a permanent home in the Museum, I would

accept the offer, with the understanding, however, that I would have

the right to withdraw it at any time after five years, if some

suitable place for its exhibition in America should present itself.”

Sir Henry Lyons contacted Orville and they began to work out the

details of transporting the plane to England. On 30 April 1925,

Orville announced that he intended to send the Flyer to England

unless the Smithsonian rescinded its position on the Hammondsport

trials – in effect ransoming the Flyer for the truth.

Walcott

responded on 4 May, reasserting the Smithsonian’s position that the

Langley Aerodrome was indeed capable of flight. Even then Orville

made an effort to keep the Flyer in America. He asked Chief Justice

William Howard Taft, who was also the Chancellor of the Smithsonian,

to convene an impartial investigation into the matter. When Taft

declined, Orville had Grover Loening carry a message to the

Smithsonian saying that he would give them the Flyer if, when they

next published their annual report, they would print both sides of

the controversy and display the Flyer in the National Museum with a

label that identified it as the first successful man-carrying

airplane.

Walcott’s

response to this was to ask two fellow members of NACA, Dr. Joseph

Ames (who had helped form the MAA) and Rear Admiral David W. Taylor

to look into the matter and make recommendations. Their report,

submitted 3 June, was a waffle – both sides of this controversy had

some validity, they decided. The Wrights had flown first, but

Langley they likened to Moses. He had led his people to the promised

land of aviation, but either through bad luck or bad design, hadn’t

been able to fly himself. Ames and Taylor’s fence-sitting was best

summed up in the wording they prescribed for a new label on the

Aerodrome exhibit:

“The Original Langley Flying Machine

of 1903 Restored.

“In the opinion of many competent

to judge, this was the first heavier than air craft in the history

of the world capable of sustained free flight under its own power,

carrying a man.

“This aircraft slightly antedated

the machine built be Wilbur and Orville Wright, which on December

17, 1903, was the first in history to accomplish sustained free

flight under its own power, carrying a man.”

Walcott made

the recommended changes to the label, but the interpretive

information displayed with the Aerodrome also included a recounting

of the 1914 Hammondsport trials and stated that the original machine

“would have flown if it had been successfully launched.” It also

said that the Aerodrome’s engine and airframe were the same in the

1914 trials as they were in 1903, and that the wings and controls

had been “reconstructed.” Orville saw the change of labels as

nothing more than smoke, meant to appear conciliatory while the

Smithsonian continued to promote the Aerodrome as the first true

airplane. If he had any doubts that his decision to send the Flyer

abroad was the best course of action, they were resolved by the

reaction of the Washington establishment in 1925.

As Orville was getting the Flyer ready to ship, Charles Walcott died

and Charles Abbot was promoted to Secretary of the Smithsonian.

Abbot had come on board in 1895 to run the Smithsonian’s

Astrophysical Laboratory. He was an ardent admirer of Langley and a

fellow solar scientist. Within weeks of his appointment he dealt

with his first Aerodrome-related crisis as Orville published his

reasons for sending the Flyer abroad, “I believe my course in

sending our Kitty Hawk machine to a foreign museum is the only way

of correcting the history of the flying machine, which by false and

misleading statements has been perverted by the Smithsonian

Institution.” Abbot quickly responded with an offer to change the

label on the Aerodrome – in fact, it was changed to one that simply

read, “Langley Aerodrome, the original Samuel Pierpont Langley

Flying Machine of 1903, Restored.” This was not enough for Orville;

a change of labels did not address the mounds of misinformation that

the Smithsonian put out beginning in 1914.

There were more such crises, and they seemed to

come in quick succession as the twenty-fifth anniversary of the

Kitty Hawk flights came and went. Senator Hiram Bingham and

Representative Lindsay Warren pushed a bill through Congress to fund

a national memorial to the Wright brothers at Kill Devil Hills,

North Carolina in 1927. In 1929, Popular Science magazine

published “The Real Fathers of Flight,” an unauthorized biography of

the Wright brothers in six parts by John R. McMahon. It was expanded

to become a book, “The Wright Brothers: The Fathers of Flight,”

in 1930. Each time the Wright story was told in the media, it

mentioned the exile of Flyer and laid the blame on the Smithsonian.

In an effort to reduce the damage that was

accumulating, Abbot published “The Relations between the Wright

Brothers and the Smithsonian Institution” just before the

twenty-fifth anniversary of the first flight in 1928. It was part

apology, part excuse, and part rationalization. In regard to the

1914 Aerodrome test flights, Abbot said, “In the opinion of some

experts, the tests demonstrated that the Langley machine of 1903

could have flown, and in the opinion of some others, these test did

not demonstrate it. It must ever be a matter of opinion.”

Unfortunately, this wasn’t Orville’s opinion. The two met on 19 April

1929 to discuss their differences and Abbot admitted there were

changes made to the Aerodrome prior to the May-June 1914 flights.

But he refused to publish them or do anything that would damage the

reputation of Charles Walcott or the Smithsonian Institution.

1934, at the

request of Charles Abbot and with the approval of Orville Wright,

Charles Lindbergh waded into the controversy in the hopes that he

could mend fences. Orville told Lindbergh and Abbot precisely what

he needed – an admission that there were changes made to the

Aerodrome prior to the May-June 1914 flights, and that these flights

did not prove it was airworthy in 1903. He produced a list of

changes, carefully winnowed so as not included any changes made

after June 1914, when the Aerodrome test flights entered their

second phase. Abbot suggested publishing a complete history,

including Langley’s work in aeronautics, the history of the

Aerodrome, Zahms’ 1914 report, Orville’s list of changes, Zahm’s

notes on Orville’s list, and all that had happened since 1914.

Orville objected; this was too complex; it obscured the heart of the

controversy. Abbot objected to publishing Orville’s list without

context. Lindbergh eventually gave up.

Lindbergh was

not the first or the last person to attempt to mediate the

Wright/Smithsonian controversy. Throughout his tenure as Secretary,

Abbot received regular correspondence asking why the Smithsonian had

not yet apologized to Orville Wright. The aviation magazine

Contact initiated a drive to petition the Smithsonian to admit

its error. Bills were introduced in Congress to investigate and

resolve the matter. A group calling themselves “Men With Wings”

organized to support the return of the Flyer to America. And

hundreds of concerned Americans, including schoolchildren, wrote the

Smithsonian to complain. This happened so frequently that Abbott

developed a “form letter” to answer these inquiries, enumerating the

things the Smithsonian had done to make amends,

The one thing the Smithsonian

could not do, however, was admit it was wrong. As late as 1941,

Abbot said as much to “Jack” Stearns Gray, an aviatrix who had

barnstormed in a Wright Model B with her husband George Gray

beginning in 1912. Mrs. Gray persisted beyond the form letter,

exchanging opinions with the Secretary several times. Abbot ended

the correspondence on 6 November 1941 writing, “It appears that the

only thing that would satisfy Dr. Wright and his partisans is for

the Institution to say it believes what it does not believe; namely,

that Langley’s plane as of 1903 was by its nature incapable of

flight. I cannot recommend the Institution publish an untruth.”

In Their Own Words

Weird Stuff

|

The Science Museum is part of a national museum complex in

Kensington, England that includes the Natural History Museum,

Victoria and Albert Museum, and others.

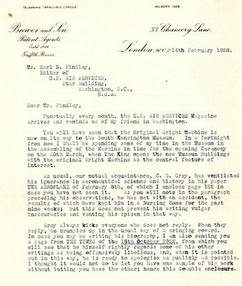

A letter to from Griffith Brewer to Earl Findlay, editor of the US

Air Service Journal, informing him that Brewer would help to

construct the 1903 Wright Flyer when it arrived at the Science

Museum in Kensington. "People from all over the world will learn

that it was not a gimcrack accident which flew to begin with, but a

machine on which all modern aeroplanes are fundamentally based,"

wrote Brewer.

Charles Greeley Abbot playing tennis on the courts behind the

Smithsonian Castle.

The 1903 Wright Flyer on display in the Kensington Science Museum in

1928.

Orville Wright (left) in 1928 at the dedication of the Wright

Brothers Memorial at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. To the right of the

plaque is Senator Hiram Bingham and Amelia Earhart.

The January 1929 edition of Popular Science began a six-part

biography of the Wright brothers. The author John R. McMahon had

visited the Orville and Katharine Wright in 1915 with another

writer, Earl Findley.

In December 1928, Boys Life Magazine published a special edition on

aviation, encouraging young men to pursue careers in the field. One

of its featured stories was "How I Learned To Fly," by Orville

Wright, Honorary Scout.

Orville Wright (left) met Charles Lindbergh (center) in 1927 when

Lindbergh landed at Wilbur Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio shortly

after Lindbergh's transatlantic flight. They quickly became friends.

The annual meeting of the National Advisory Council for Aeronautics

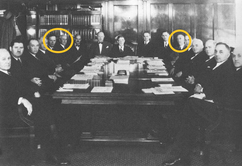

(NACA) in 1939. Charles Lindbergh and Orville Wright are seated together on

the left; Charles Abbot is on the right.

George and Jack Gray barnstorming together in Florida in 1915.

|