|

Up

Up

Bell's Boys

Bell's Boys

(You are here.)

Down

Down

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

hile

Wilbur and Orville were in Europe, a group of aviation enthusiasts came

together in America that would give the Wrights a run for their money.

Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, had a passionate

interest in aviation and had experimented with scientific kites since

1891. He was also a good friend of the Dr. Samuel P. Langley, the lately

deceased head of the Smithsonian and builder of the unsuccessful Aerodrome.

In many ways, Bell was Langley's successor – a Washington insider

determined to develop a practical airplane with the apparent blessing of

the U.S. Army. hile

Wilbur and Orville were in Europe, a group of aviation enthusiasts came

together in America that would give the Wrights a run for their money.

Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, had a passionate

interest in aviation and had experimented with scientific kites since

1891. He was also a good friend of the Dr. Samuel P. Langley, the lately

deceased head of the Smithsonian and builder of the unsuccessful Aerodrome.

In many ways, Bell was Langley's successor – a Washington insider

determined to develop a practical airplane with the apparent blessing of

the U.S. Army.

Over the summer and fall of 1907, he organized the Aerial Experiment Association to

build a practical airplane. It was a small group. Bell and his wife Mabel

first

enlisted engineering student John McCurdy and balloonist Fredrick W.

"Casey" Baldwin.

Next came Army aviation expert Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, who had been

recently joined the new Aeronautical Division of the U.S. Army Signal

Corps. Bell pulled a big string, asking his friend President Theodore

Roosevelt to reassign Selfridge to the A.E.A. The

last to join was motorcycle manufacturer Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss had

recently build several motors for Bell and Thomas Baldwin (no relation to

Casey) to use in aviation

projects. (He had offered his motors to the Wright Brothers in 1906, but

they had declined.) Mabel Bell funded the group for $20,000.

"Bell's Boys," as they became known, began work on Bell's

estate in Beinn Bhreagh, Nova Scotia. The members of the A.E.A. had

agreed amongst themselves that each would have a chance to design an

airplane, building on each others' discoveries and mistakes. The caveat

was that they first had to test Bell's Cygnet, a huge manned kite

52 feet (15.8 meters) wide and 10 feet (3 meters) tall, made up of 3,393

tetrahedral cells and covered on two sides in red silk. Bell had the

silk dyed red because he believed it stood out better in photographs,

and he was determined to document the progress of the Cygnet in

photos.

In the center of these cells was a tunnel for a man to lay prone

and room behind him for an engine and propeller. Bell's boys fitted

pontoons to the huge kite and on 3 December 1907and towed it behind

a small steam launch across Baddeck Bay, where it made a successful

tethered flight without a pilot or propulsion. Three days later,

Selfridge crawled into the tunnel to make a manned glider flight –

the A.E.A. had still not added the motor or propeller. The Cygnet

soared to an altitude of 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 meters) while

towed behind a steamer. But when it descended, Selfridge failed to

release the towline. From his tunnel, he could no see well enough to

know that he was approaching the water. The big kite was dragged

through the water and torn to pieces. Fortunately, Selfridge escaped

unharmed.

After the Cygnet tests, Glenn Curtiss convinced the group

to move their operations to Hammondsport, New York, where he had a

factory, machine tools, and a slightly warmer climate. During the

move – in December of 1907 and January of 1908

– Bell's boys gathered all the

information they could on aviation and aeronautical engineering,

similar to the literature search the Wrights had done when then

began their glider experiments in 1899. In fact, Curtiss and

Selfridge wrote to the Wright brothers, asking advice. The Wrights

were as candid with the A.E.A. as the Smithsonian had been with

them. They answered questions about engineering and materials, and

directed the members to

published papers and patents for more in-depth information. They thought

well of Alexander Graham Bell, and it impressed

Wilbur and Orville that he was in charge of this little group.

When McCurdy, Baldwin, Selfridge, Curtiss, and Bell. reconvened

in Hammondsport, they built a small glider patterned after the

Wright design, as well as a modified Chanute-Herring glider. The

younger men made about 500 glides with these aircraft on the snowy

slopes of the hills surrounding Hammondsport, teaching themselves to

fly in unpowered gliders just as the Wrights had done at Kitty Hawk.

While they were doing so, they built their first powered airplane.

It was called the Red Wing as it was covered with red silk left

left over from the Cygnet project. It

was a biplane, built after the Wright pattern with an elevator in front

and a rudder in back. However, the designer – Selfridge –

added a

second elevator in back. He trussed the wings, curving the top wing down

and the bottom wing up so the wing tips almost met. This, the A.E.A.

members reasoned, would provide greater structural strength. It was also

hoped that it would provide lateral stability, as the airplane had no roll

control. It was towed out on the ice of Lake Keuka on 12 March 1908, and

it fell to Casey Baldwin to act as pilot since Selfridge was away on

Army business. To the surprise of all, he got the airplane off the

ground on the first try, flying it 319 feet (97 meters) before the tail

collapsed and it crash-landed. Bell's boys tried again on March 17, but

the wings were soaked by a spring rain. The Red Wing flew just

120 feet (37 meters) before auguring in on its left wing. This time the

crash completely wrecked the airplane.

Far from being disappointed, the A.E.A. was encouraged by the

performance of the Red Wing. and immediately began work on their second airplane,

this one, designed by Casey Baldwin. They had only enough red

silk left to cover the tail of the new airplane; the remaining surfaces

were covered in white silk that gave the aircraft its name: White

Wing. The design was very similar to Selfridge's Red Wing, but Baldwin added

ailerons for roll control. He also installed wheels on the skids, as the

ice was fast disappearing on Lake Keuka. Baldwin, Selfridge, McCurdy,

and Curtiss all flew it at a trotting track near Hammondsport between

May18 and 23 of 1908. Curtiss turned in the best

performance, flying 1017 feet (310 meters). On its last flight, the White Wing

flipped over and was badly damaged. The group gamely began work on a third airplane.

In Their Own Words

- Letter to Mabel --

Alexander Graham Bell was keenly interested in the Wright brothers

long before he began the Aerial Experiment Association, as this letter

to his wife in 1906 shows.

|

The Aerial Experiment Association left to right: Glenn Curtiss, John

McCurdy, Alexander Graham Bell, Fredrick Baldwin, and Lt. Thomas

Selfridge.

The Cygnet I manned tetrahedral

kite mounted on pontoons in from of Bell's boat house in Beinn Bhreagh.

AEA members experiment with an oversize copy of

the Chanute-Herring Glider.

The Red Wing rests on its skids on the frozen

surface of Lake Keuka. The top photo is a side view and the bottom photo

(with the postmark) shows it from the front.

The Red Wing was nearly

destroyed after its second flight.

The White Wing in flight on May 23, 1908.

A close-up of the White Wing, showing its

Curtiss engine.

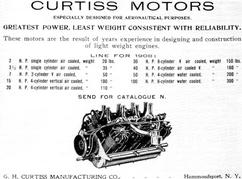

By the time he joined the AEA, Curtiss was already

manufacturing motor designed for aeronautics, as this 1908 ad shows.

|