|

Up

Up

Landed Gentry

Landed Gentry

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Espańol, Portuguęs, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

Sir John Wright, Lord of Kelvedon

Hall, circa 1485 to 1551

Sir John Wright was born in Dagenham, Essex

County, England. He married Olive Hubbard in the South Weald Church,

Essex County (near Wrightsbridge) on 17 March 1508. Olive had also

been born in Dagenham. They had seven children – John the Elder,

Katherine, Robert, Alice, John the Myddle, John the Younger, and

Elizabeth. As Henry VIII ascended the throne, he granted John Wright

peerage on 20 June 1509, giving him a title and seat in the House of Lords. John became a

baron and took the title Sir John Wright. He was also granted a coat

of arms – an azure shield with silver bars and a leopard’s head. The

family motto was “Conscia recti,” a Latin phrase from Aeneid

meaning “a clear conscience.”

Sir John personally served King Henry VIII

during the “King’s Great Matter,” during which Henry petitioned Pope

Clement VII to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Catherine

had not produced an heir to his throne, and Henry asked the Pope to

give him leave to marry Ann Boleyn, his mistress and a lady in

Catherine’s entourage. The Pope refused, and Henry severed the

Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church in 1533. Whatever

Sir John’s role was in this event, it pleased the King and John

became a rich man for his efforts. He turned his attention to

building a suitable home for a man of his means and station.

Sometime before 1509, John had moved to

Kelvedon Hatch with his father. The Doomsday Book, a census ordered

by King William I in 1086, mentions Kelvenduna, a feudal

estate lorded over by a Saxon soldier/sailor, Aethelric. It’s

thought that Aethelric may have built St. Nicholas, the oldest

surviving church in the area. In 1066, Aethelric had sailed off to

fight William the Conqueror, the Wryta brothers, and other Norman

invaders. The defeated Aethelric returned to Kelvenduna and

continued as lord of the manor under William I. Not long afterwards,

however, he fell ill and died. His property passed to the church,

probably confiscated by King William, as William did with many

Saxon freeholders who fought against him. The ownership of the Kelvenduna estate passed to “St Peter” – the Norman arm of the Roman

Catholic Church headquartered in Westminster Abbey. Specifically, it

passed to Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux and William’s half-brother. This

was William’s way of keeping the spoils of war in the family.

John erected Kelvedon Hall next to the old Saxon church allegedly built by Aethelric. Its construction took 14 years, beginning in 1524. In

1538, he bought the surrounding lands – about 2000 acres – from

Richard Bolles and Westminster Abbey for ₤493. Bolles had inherited

the tenancy of the lands from his mother’s family, the Multons, who

had in turn been granted the tenancy in 1225 from Westminster Abbey.

This real estate deal reeked of politics. The transfer of lands from

the church to the loyal gentry was part of Henry’s campaign to

weaken the power of the Roman Catholic Church in England. Sir John

Wright II died in Kelvedon Hall on 5 October 1551. His wife Lady

Olive Hubbard Wright died in Kelvedon Hatch on 22 June 1560.

John (the Myddle) Wright, 1522 to

1558

Middle John Wright was born in Kelvedon Hall in

1522. According to his father’s will, executed in 1551, “To my son

called Myddle John I give all the land I have in Havering and houses

and millers house and a tenement in Childerditch wherein Gibbes doth

dwell.” This was the area where the bridge that the Wrights

had tended for centuries spanned the Ingrebourne River. The land was known as Wrightsbridge,

and the

manor house and estate was referred to both as Wrightsbridge Manor

and Dagenham Manor.

During his time, Englishmen identified each

other less and less as Norman and Saxon and became much more

concerned with who was Catholic and who was Protestant (Anglican).

Middle John and his siblings were mostly Protestant, their father

having supported Henry VIII’s break with Rome. But in 1553, just

before Middle John’s death, Henry VIII’s daughter Mary I (1553-1558)

came to the throne and pressed for England to return to Catholicism.

She was ruthless in this endeavor, had over 280 Protestant

dissenters burned at the stake, and earned the sobriquet “Bloody

Mary.” Fortunately for the Wrights and other Protestants, her reign

was short and the persecution ended when her Protestant sister

Elizabeth I (1558-1603) came to the throne. But it was a harbinger

of things to come; the tensions between religious sects in England

continued to grow.

Middle John married Alice Rucke of Kelvedon

Hatch in 1541. They had six children, Dorothy, John, Mary, Olive,

Agnes, and Robert. Middle John died in Wrightsbridge in 1558 when he

was just 36 years old. His wife Alice did not live much longer; she

died in 1560.

Lord John Wright of

Wrightsbridge,

1548 to 1624

Middle John’s first son, John Wright, was born

in 1548 and inherited the Wrightsbridge lands and Dagenham Manor

when he was just 10 years old. He was granted peerage by Queen

Elizabeth I (1558-1603) in 1590 and given a seat in the House of

Lords. He was married twice, the first time to Elizabeth Linsell

about 1568. She bore him three sons and two daughters – John,

Samuel, Jane, Nathaniel, and Elizabeth. His first wife died in 1589

and John married Bennett Greene in 1590.He had three more children

with her – Lawrence, Bennett, and William.

They lived in auspicious times, Elizabethan

England was a foment of new ideas and opportunities. Francis Bacon

codified the Scientific Method, William Harvey mapped the

circulatory system, and Sir Francis Drake sailed around the world.

In 1587, the English took an interest in colonizing America and

finally succeeded in 1607. The King James Bible was published in

1611, making this book available in English for the first time.

England’s agrarian economy expanded to include large-scale

manufacturing and global trade. Young men left the rural manors and

filled the cities, becoming doctors, lawyers, and merchants. From

these new urban professionals emerged a literate middle class who

devoured the plays of Shakespeare and the books of Milton and loudly

debated the finer points of politics, philosophy, and religion.

Among these new ideas was Puritanism. Henry

VIII’s break with the Pope had been welcome in England not because

the English wanted their King to have his marriage annulled, but

because of the excesses and the failures of the Catholic Church. The

Church of England was the beginning of the Reformation in England,

but many felt it did not reform enough. The Anglican church retained

much of the pomp and ceremony of the Catholic church it had

replaced. More important, the rigid clerical hierarchy remained –

the King and had simply replaced the Pope. Moreover, English

protestants who fled to other countries during the reign of Mary I

brought back to England the ideas of John Calvin and other

contemporary theologians. This stew of religious ideas gave rise to

the Puritans, who emerged

largely from the new English middle class. As a group, they proposed less pomp and more

substance. They rejected the hierarchy and the notion of a supreme

spiritual leader to whom they owed allegiance. They wanted their

congregations to have more autonomy and their God to be more

accessible. At least two of Lord Wright’s sons, John and Nathaniel,

had strong Puritan leanings.

Lord John Wright died at Wrightsbridge in 1624

as the Puritan movement reached its strongest ebb – and a year

before they faced their greatest challenge.

John Wright, Esq., 1569 to 1640

John Wright was born in 1569 at Wrightsbridge,

Essex County, England. Although firstborn, there is no record that

he inherited the Wrightsbridge lands or Dagenham manor. Instead, he

seems to have had a successful career in London. He graduated from

Emmanuel College at Cambridge University (a hotbed of Puritan

radicals) in 1593 and was admitted as a barrister to Gray’s Inn (an

influential legal association) in 1598, and began a clerkship in the

Courts that same year. He married Martha Castell in 1594, and they

had four sons – John, Nathaniel, Samuel, and Robert. Martha died in

1610 and John remarried to Fortune (Garraway) Blount, the widow of

Sir Edward Blount, in 1618. John and Fortune had one child, James.

In 1612 John Wright, Esq. was appointed a clerk

to the House of Commons. Because of this appointment – and because

he was a Puritan-leaning Protestant – he was probably at odds with

his Anglican father in the House of Lords from time to time. It was

a frustrating time for any member of the government; King James I

(1603-1625) steadfastly refused to share any real power with

Parliament. A Parliamentary document protesting the actions of King

James I bears John Wright's signature on it in his capacity as clerk

of the House of Commons. This display of opposition to the King by a

family member would no doubt have embarrassed a Peer of the House of

Lords. We don’t know how well John got along with his father, but if

they had religious and political differences this may explain why

John did not inherit his father’s land, at least in part.

Goings on outside Parliament may have also

strained the relationship between father and son. While Puritans

weren’t put to death for their beliefs, they weren’t well-tolerated

by Anglicans. They were blocked again and again from making reforms

to the Church of England and some Anglican bishops openly oppressed

Puritan-leaning ministers and congregations. Anti-Puritan sentiment

within the government and the Church of England was controlled under

King James I (1603-1625), but it was unleashed when his son Charles

I (1625-1649) took the throne. He permanently dissolved the

Parliament in 1629 and what had been an extremely difficult situation

for Puritans in England became hopeless. Puritans began to emigrate

to less hostile lands. In 1630, Puritans obtained a royal charter to

form the Massachusetts Bay Colony. John’s brother Nathaniel was a

charter member and 1/8 owner of the Arabella, flagship of the

fleet that carried Puritans to the New World. John’s son Samuel was

among those who sailed. John Wright, Esq. remained and died in

Dagenham in 1640, only a few years after Samuel left for America.

|

A print of Kelvedon Hall in 1777 showing St. Nicholas Church nearby.

The church was abandoned in 1895 although its ruins still stand on

the property.

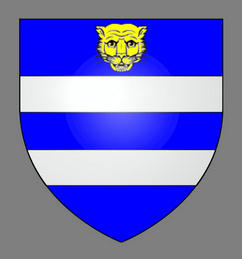

The Wright Coat of Arms, granted at the beginning of the reign of

Henry VIII. Heraldic leopards were actually lions –

"lion passant guardant" –

with their heads turned toward the observer.

Kelvedon Hall today. The manor was purchased by American-born author

and statesman Henry Channon in 1938 and is still in the

Channon family. To visit the hall on Google Earth, click

HERE.

Photo courtesy

History House.

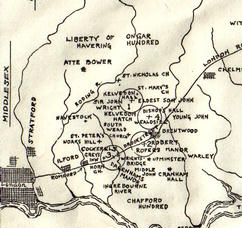

This map shows the locations of the four estates owned by Sir John

Wright. Each of his sons inherited an estate in 1551 – Middle John

got Dagenham Manor.

Queen Mary I – "Bloody Mary."

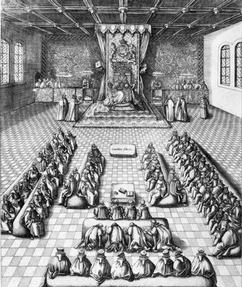

Queen Elizabeth presides over the House of Lords, Lord John Wright

somewhere amongst them. Peerage was not a taxing responsibility.

During the 45 years that Elizabeth ruled, Parliament was in session

for about 3 years all totaled.

A map of the route that Sir Francis Drake took around the world with

a profile of his flagship, the "Golden Hind." Drake's voyage was

financed by Elizabeth I. During the voyage, he captured a Spanish

treasure ship and the captured gold made Elizabeth a 4700% profit on

her investment.

In John Wright's day, Emmanuel College was a new school in an old

building – it had been a monastery until Henry VIII confiscated the

building and grounds from the Dominican Friars. It was purchased in

1584 to house the college. John was a member of the second

graduating class.

The Great Hall at Gray's Inn. Shakespeare performed here while John

was a member.

|