|

Up

Up

The June Bug

The June Bug

(You are here.)

Need

to Need

to

find your

bearings?

Try

these

navigation aids:

If

this is your first

visit, please stop by:

Something

to share?

Please:

|

|

Available in Française, Español, Português, Deutsch, Россию,

中文,

日本, and others.

n

the summer of 1908, the Wright brothers were well ahead of any

other group of aeronautical experimenters on the planet by virtue of having

developed a practical,

passenger-carrying airplane. But news of their success had motivated other

talented and determined engineers, and some of these were catching

up. The next important aviation

milestone was passed not by the Wrights, but by the new kids on the

aviation block, the Aerial Experiment Association under the guidance of

Alexander Graham Bell – "Bell's Boys" as they were sometimes called. n

the summer of 1908, the Wright brothers were well ahead of any

other group of aeronautical experimenters on the planet by virtue of having

developed a practical,

passenger-carrying airplane. But news of their success had motivated other

talented and determined engineers, and some of these were catching

up. The next important aviation

milestone was passed not by the Wrights, but by the new kids on the

aviation block, the Aerial Experiment Association under the guidance of

Alexander Graham Bell – "Bell's Boys" as they were sometimes called.

Mindful of how prizes had helped spur European aviation, the Aero Club

of America and Scientific American magazine partnered to offer their own

incentive – a silver sculpture called the Scientific American

Trophy.

This sculpture would be awarded each year to recognize a significant

achievement in aviation, they announced. When they unveiled the prize in 1907, the Aero

Club announced that they would award it for the first time to the first

individual to fly a kilometer in a straight line.

This was a "gimmee" for the Wright brothers, or so the

presenters

thought. Scientific American magazine had initially been skeptical

of the Wright claims, and the editors were now anxious to mend fences with

the inventors as their work drew more attention. The Aero Club had been

supportive of the Wrights since the club's outset. They had been among the

first to investigate the Wright's claims, then endorse them as the

first to develop an airworthy aircraft. Many in the club counted

themselves as supporters, even good friends of the Wrights. Allan Hawly, the

president of the club,

had treated Wilbur to a balloon ride when they met in France.

Bell's Boys completed their third aircraft in the late spring of 1908,

the first designed by Glenn Curtiss. Like the White Wing, it had

ailerons, a rudder, and front and back elevators. Unlike previous AEA

aircraft, it wasn't called after the color of the cloth used to cover the

wings. Instead, Glenn Curtiss gave the honor of naming the aircraft to

Mrs. Malinda Bennitt, a friend who had helped him out when he was just

starting his manufacturing business. The gesture so flustered her that

"my old head just wouldn't work." Alexander Graham Bell came to

her rescue, and for reasons lost to history, he picked "June

Bug" – perhaps because it was

completed in June.

This was also the first AEA airplane that wasn't covered in

closely-woven silk. It used a fine weave of cotton and the

Association members were amazed at the difference in performance. On

20 June 1908, they made three attempts to get the June Bug

off the ground with no success. They reasoned that air was bleeding

through the cloth, reducing lift. Their solution was to treat the

wings with a mixture of gasoline and paraffin to seal the fabric.

This mixture was called "canvas paint" and had long been employed by

sailors to seal their sails, making them more aerodynamically

efficient as well as less susceptible to mildew. The Wright brothers

almost certainly used something similar while experimenting in Kitty

Hawk, but this was the first recorded use of what would later be

called "wing dope."

Curtiss made three successful flights in the June Bug on June

21, and within a week he was breaking his own records with flights of over

1000 yards (914 meters). The AEA was within spitting distance of flying a

kilometer. Satisfied that they could capture the Scientific

American Trophy, they cabled the Aero Club that they would make a run for it on

July 4.

The request caught the Aero Club by surprise, and the secretary, August

Post, informed Charles Munn, the publisher of Scientific American. Munn

cabled Orville, offering to postpone the AEA attempt if Orville wanted

to try for the trophy himself. Orville, unfortunately, was swamped. He,

Charlie Taylor, and Charlie Furnas were working around the clock trying to

get an aircraft ready to fly for the U.S. Army trials. On top of that,

Wilbur had asked him to write

an article for

The Century magazine that

would help establish their position as the first to make a controlled,

sustained flight in a powered aircraft. Finally, the Aero Club rules said

the plane had to make an unassisted take-off. With everything else

he had to do, Orville would have to put wheels on his airplane and find a

field big enough to make a take-off run. He declined.

Twenty-two members of the Aero Club arrived in Hammondsport, New York

on July 4 to witness Curtiss's flight, among them

Charles Manly who had piloted the unsuccessful Langley Aerodrome in

1903 and

Augustus Herring who, with Octave Chanute, had developed the

milestone Chanute-Herring glider of 1896. The AEA had laid out a course

of flight, beginning at a racetrack and continuing over clear, level

fields. A flag marked the distance of one kilometer from the starting

point. The mood at Hammondsport was festive but the weather was uncooperative;

winds and rain delayed the flight until well into the evening. At 7:00

p.m., Curtiss took off in the June Bug, climbed to an altitude of

40 feet, and landed immediately – the airplane had been rigged

incorrectly, making it impossible to keep the nose up. After adjusting the

rigging, he flew again. Curtiss later described the flight:

"When I gave the word to let go, the June Bug skimmed along over

the old race track for perhaps two hundred feet, and then rose

gracefully into the air. The crowd set up a hearty cheer, as I was

told later, for I could hear nothing but the roar of the motor, and

I saw nothing but the course and the flag marking the distance of

one kilometer. The flag was quickly reached and passed, and still I

kept the airplane up, flying as far as the open field would permit,

and finally coming safely down in a meadow, fully a mile from the

starting place. I had thus exceeded the requirements, and had won

the Scientific American Trophy for the first time."

When the distance was totaled, Curtiss had traveled 5,360 feet

(1634 meters) in 1 minute and 40 seconds. He was the toast

of both the American and European newspapers.

The Wrights, even though they had declined to compete for the trophy,

did not fail to take notice. Orville wrote a stern note to Curtiss on July

20, reminding him that he and Wilbur had shared information with the AEA

freely. The Wrights would allow them to use the patented control system

for experimentation, but Orville warned, "We did not intend to give

permission to use the patented features of our machines for exhibitions or

in a commercial way." It was the first of many such communications

that the Wrights would exchange with Curtiss.

|

The 1908 Scientific American

Trophy. Note the Langley Aerodrome on the globe.

Assembling the June Bug

in a tent hangar.

Roll out of the completed

June Bug.

Glenn Curtiss in the cockpit of the

June Bug.

The June Bug in flight on July 4, 1908.

Curtiss and other "Bell's Boys" gathered

around the June Big after a triumphant flight.

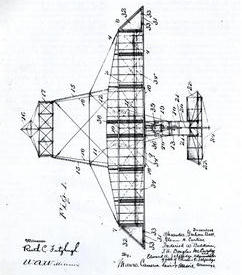

The patent drawing for the June Bug. Nos. 32

are the triangular ailerons the AEA used for roll control.

After successfully capturing the

Scientific America Trophy, the AEA made an unsuccessful attempt

to covert the June Bug into a

hydroplane. The airframe was mounted on pontoons and given a new name --

the Loon. The unstepped design

of the pontoons and the lack of power made it impossible for the

Loon to separate from the

surface of the water, but this was nonetheless one of the first serious

experiments with hydroplanes in America. |